Yes, I have decided to leave the Broad Institute.

“Are you crazy?” 🤯

Well, I think there are many good reasons for it and I will try to explain why. But, before I go into the why, let’s talk about the last 1.5 years at Broad and what I have been able to do. 🔍

3.5 years at the Broad

There have been quite some changes and many successes in the recent year. I have finished my main research project at DFCI with Maxim Pimkin and I have now been 100% a Broadie. ![]()

My two main projects have been on what I liked to call CCLE3 and Celligner2.

DepMap Omics: CCLE3

At CDS, some people have come and gone, mainly someone joined my team: Simone Zhang. Taking more Engineering responsibilities from me and helping me on the depmap-omics project. 💪

I was also quickly promoted to Senior Associate Computational Biologist. The last ladder before becoming a Research Scientist at Broad. Simone coming was also given to me as a way to show my ability to coach and be a mentor to a junior scientist.

This allowed us to define a lot more avenues of research, which I packaged into a project called: CCLE3. 💡

The main question was: “What can we do with the data we have at the Broad, in depmap-omics, to help the community?”

I was proud to be given the responsibility of presenting this vision to the Cancer Program leadership in 2021. Here is the presentation I gave:

Mostly one can see that it was axed around the idea of generating novel features from omics data we already have, improving the metadata, and harmonizing our omics. having the same sequencing data across all our samples -at least for RNAseq & WGS-. 🟩

I strongly believed -and still do- that these were the low-hanging fruits 🥝 for us, allowing us to discover new targets cheaply and squeeze more value out of our current database.

Let me present that in more detail.

new features

I believe that in the last 2 years, we have made an impact on the community by open-sourcing our toolkit and making our data reproducible and more generally available. 📖

However, from all the fancy Machine Learning and prediction tools we have tried and designed to make better predictions of gene dependency & cancer targets. Almost every time, without a doubt, nothing had a greater impact than generating a new genomic feature from our dataset. 🤯

I think this is a big “lessons learned”, for me at least. That data comes first and domain knowledge comes second. I think this is a lesson that is not only true for genomics but for all data science.

Let me present some of the new features we have developed:

-

Recreating & improving the microsatellite instabilities from DNAseq –> initially lead to the WRN / MSI paper.

-

Associating features based on gene sets, gene proximity, etc.. –> initially lead to the 2022 VPS4A/VPS4B paper

-

Getting info about viral infection of the tumor sample.

-

Getting at somatic & germline structural variants from WES and WGS and associating them with fusion variants in RNAseq –> Lead to a new paper with the Rameen Beroukhim lab.

-

getting info about splicing QTLs using spliceAI on mutation data and associating them with transcript abundance –> paper in progress as of 2023 also with the Beroukhim lab.

-

getting info about the global functional status of genes (based on CNV/SV/SNPs/ INDELS/ etc) and their phasing and expression –> has already been shown to improve most of our dependency prediction data.

-

Germline mutations & their associations to dependency –> something I pushed for a lot. And led to a couple papers on ancestry bias with Sean Misek and improvement of our Achilles Algorithm.

The last project is one which I was really proud 🥇 of as it is something I had pushed for two years without much success.

Until Sean, a new research scientist in the Beroukhim lab, was able to help me convince the rest of the team that this would be a worthwhile endeavor.

During Broad’s 2021 Retreat, I was able to present this work to the whole Broad community. Here is the poster:

I am sad that despite publishing a couple of first-author papers and being part of a dozen other collaborations, 🙄 I was not able to see from that even a hint of a CCLE3 paper. I hope it will be published someday but I have been told that to be guaranteed a Nature, one needs more than new features and new predictions, one -apparently- also needs a crazy new sequencing dataset 🗻 (a la Broad).

metadata improvement

MetaData had always been one of our Achilles’ heel. We knew they were not great but we also knew that no one had great metadata for their cell line. What made the group become quickly convinced to start working on it, was how much better any improvement made the prediction algorithm work. Seeing that we started running many parallel efforts to map duplicate samples (using genomics), similar-looking models (using transcriptomics), sex, age, etc. ![]()

Moreover, we started merging our cell line annotations with Cellosaurus to discover more issues in both our databases and started merging our disease annotations with the NCIT to realize that many more cancers than we thought were related in some way. or were simply improbable annotations. 🧭

This effort is also something I had pushed for, for a while, and reused many of the improvements I had already put forward. This is also something I am proud of. I think it is a great example of how such a small, boring effort can have a big impact on science and therapeutic discovery.

next steps for sequencing

Moreover, since it is the Broad, in 2019 we had goals of going 10x in the coming years. However, we soon realize that there were not a lot of “good” models left 🪹 and that our capacity for creating them was very limited. We wanted more cell lines / 3D models but it was hard to get good ones.

Given that we have 12 different sequencing data types for 1700 lines but almost none of them have all of those sequencing 🧬 done, our first goal was to do WGS & RNAseq on everything. representing more than 200 RNAseq and 1000 WGS, the reordering of 400 lines, and the likely drop of dozens of lines that do not exist anymore.

Why do that?

Because these are the low-hanging fruits for us. Without changing anything, without generating new models, and changing pipelines and platform, we just get a lot more information allowing us to discover new targets cheaply and squeeze more value out of our current database. When your model can work on modality A+B+C but only 300 samples / 1700 have each of those modalities, you are missing out on a lot of potential. 🟩

But a second objective. Even more ambitious came to us in the form of Jason Buenrostro: Inventor of ATACseq & SHARE-seq. Jason wanted to apply SHARE-seq to all our cell lines. likely millions of cells. Then, apply it for post-perturbation 🔫. This would allow us to see the effect of a drug on the chromatin accessibility of a cell line and its expression at single-cell resolution. This was a very exciting project. And I was tasked to coordinate it on the CDS side by Paquita Vazquez.

However, this was not all, and the other half of my time was also spent on a pet peeve of mine: Celligner.

Celligner2 and the hint of foundational models

Celligner was initially developed by Allie Warren. Its goal is to align bulk RNAseq data from cancer models (CCLE) with data from patients’ tumors (TCGA). Comparing the two 🍎 / 🍊 to:

- assess annotation quality.

- assess model quality as its similarity to the patient’s tumor.

- assess model coverage & diversity.

Initially, they don’t align well and one needs to apply an alignment method for those datasets to work together.

She did that by reusing the MNN tool from Seurat and adding in additional preprocessing using contrastive PCA, differential expression, etc.

The project work very well and led to a lot of excitement.

As Allie left, I took over the project and started working on a new version of the tool. I wanted to answer biologists’ needs. Initially by adding new features and making the tool more scalable.

But I soon started to think that we could do so much more by using a different approach.

Reusing VAE-based autoencoders like scVI and scArches and training them to make a model look like a tumor and vice versa. Training them to predict features like tumor type, sex, and age. And using explainable AI (XAI) 🗨️ to understand what the model was learning and what gene sets and pathways were explaining these features.

We actually went pretty far with this and I started making early presentations for the team. 🧑🔬

I think I showed many interesting results that could have fit into a paper.

Senior Members were intrigued by 2 ideas:

- using annotations during training as semi-supervision constraints to improve model quality.

- using additional data like GTEX that was containing normal samples as a way to also improve model quality. 💹

For the first part, the debate was mostly around: “What if the annotation is wrong?”, “what about overfitting to annotations?”, “it seems like using what you will test your model on”…

But I was able to show that since it was only part of the loss function, it was not leading to this issue. By making wrongful annotations, up to a point, the model was able to still create the right mapping (e.g. fake “lung models” 🫁 that were actually “breast models” were still aligning with breast cancer). Moreover adding these annotations was in fact improving the model quality, and quality here is defined not by annotation but by many other metrics 📈 as shown in the scIB package.

For the second part, it just seemed nonsensical to some to use data that was not cancer: “What does it mean to align normals to cancer?”, “Is it really useful?”, “Why do you want to do this?”

I think here I had the first hint of what would soon be the foundation models in scRNAseq that would come out in the following year. I was seeing Gtex as pretraining. Helping the neural network to also learn how genes are related and differences in tissues. I was seeing it as a way to make the model more robust and more generalizable. 🧠 It showed in the metrics that doing that was improving the model on every downstream tasks. It was also interesting to see cancers that were mapping to their original tissue of origin and the ones that were completely diverging. 📉

The Celligner project was going well, the results were there. However many changes at CDS and Broad came together to slowly end it.

Leaving Broad

In the last year at Broad 3 prominent colleagues left Broad: CDS founder Aviad Tsherniak, CDS director James McFarland, and Javad Noorbakhsh. This departure of multiple colleagues was a lot but it was also the only 3 people pushing for Celligner and bringing more AI in CDS.

Moreover, there was a change in the cancer program leadership itself. With Eric Lander, Broad’s Director leaving for Senate 🇺🇸 (and then quickly leaving 🙊 ). Todd Golub became Broad’s new director and Bill Sellers, a world-renowned cancer scientist from Novartis and heavily involved in CCLE and DepMap, became the new cancer program’s director ♋ .

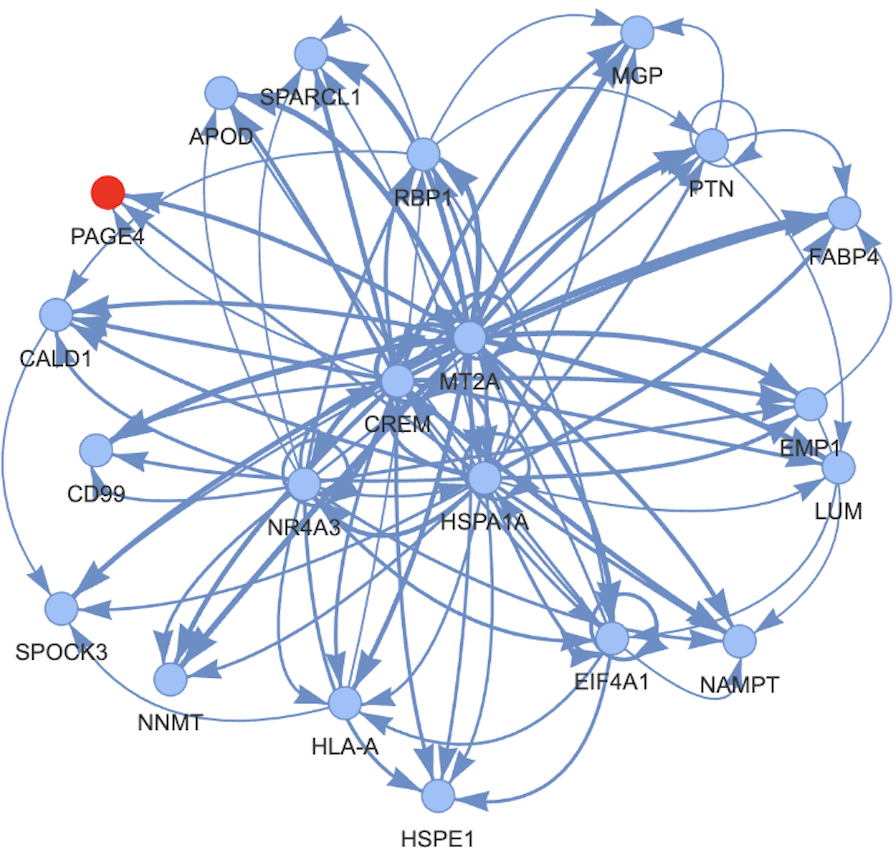

Bill wanted to rationalize a bit more the objectives of the Cancer Program toward drug discovery. And he wanted to do that by focusing on a few key areas ![]() . This meant that some projects were going to be stopped and some others were going to be prioritized. So you can guess where this is going for Celligner… 🛑

. This meant that some projects were going to be stopped and some others were going to be prioritized. So you can guess where this is going for Celligner… 🛑

But the new projects were still very exciting. But other factors were very important in my decision too. I was missing my family, my father was ill, I could see that life was moving fast for my siblings and my friends. I felt that I had to take a life decision: I had to make a choice and decided to move back to France. 🇫🇷

I won’t take you through covid’s time and my SO being away too (see 2 years at Broad) but everything played a role.

What’s next?

I also got a sense that I need to see drug development firsthand. I need to get back in the weeds of building a company and a project. I spent a year doing that before Broad and such a fast-paced. product-first 📦 environment is also something that I am missing. I will try to see what I can do in the field of target discovery with this acquired knowledge.

In no time I got into this up-and-coming French StartUp called Aqemia. Let’s see what is next.

If you want to see what I presented to the companies 🏛️ I have applied to. Here is my interview presentation, used in a couple fancy companies’ interview 😁.

Leave a comment